The Evolution of Modern Psychedelic Art

From Indigenous art to trippy Instagram visuals and everything in between, here’s a breakdown of the history of modern psychedelic art.

I am staring ahead at two tigers leaping through the sky, approaching a naked woman who is lying blissfully unaware on a floating block of ice. It is Dali’s famous 1944 painting, succinctly titled, “Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening.”

A year before this painting was completed, on April 19, 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first ingested LSD and discovered its psychedelic properties.

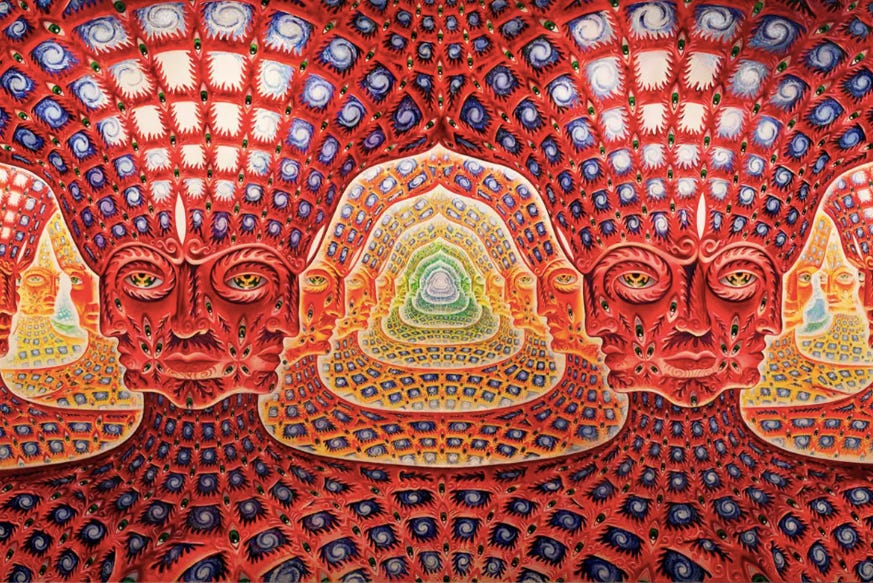

I looked on at this painting and wondered what has shaped the psychedelic art evolution. How did we go from the surrealist movement that began in the early 1920s, with Magritte and Miro, to Alex and Allyson Greys’ Chapel of Sacred Mirrors, or Beeple’s social commentary through absurd imagery? How has our mode of consuming this very art changed – from psychedelic rock posters and albums of the 1960s to trippy images produced for Instagram? How has the art of Indigenous cultures influenced and shaped the art we turn to today?

First, I want to define what we mean by “psychedelic art.” Any piece of artwork can feel psychedelic. If you take a tab of acid and head to an art museum, that will certainly help. But what makes a piece feel inherently psychedelic relies on two factors: the distinctive, uniquely colorful style and composition, as well as the feeling that arises from a familiar idea or reality being subverted. It forces you to look at the world, as well as yourself, from a new perspective, and feel more deeply connected to the universe around you.

So, how is this art created? Artist Allyson Grey tells me, “a psychonaut may have a vision filled with brilliance and personal meaning and may feel compelled to mark that essential visionary moment in a work of creativity. If they are skilled, the portrayal may be considered great Visionary or Psychedelic Art.” The term, “Visionary Art” is the broader category, she explains, as it “describes art that depicts a person’s Mystical Encounter, an unforgettable meeting with the Divine. The earliest artwork, cave art, reports ancient brushes with visionary realms.”

British psychologist and researcher Humphry Osmond coined the term “psychedelic” in 1956 at a meeting of the New York Academy of Sciences, describing the word to mean “mind-manifesting.” The word comes from the Greek words psyche (mind) and delos (manifest), implying that psychedelics can reveal the human mind’s unused potential. By that definition, all artistic efforts to depict the inner world of the psyche may be considered “psychedelic.”

But psychedelic art has deep roots in the artistic and spiritual traditions of many Indigenous cultures, long before the term “psychedelic” even first came into use.

Psychedelic Art Traditions within Indigenous Cultures

In Indigenous cultures in Peru, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador, there is art centered around Ayahuasca, which features complex geometric patterns and shapes representing the interconnectedness of life. Amazonian tribes, like the Shipibo-Conibo of Peru, create intricate visual patterns that reflect the visions and insights gained during ayahuasca ceremonies. The patterns represent the “Icaros” (healing songs) sung by shamans during ceremonies and are seen as a form of communication with the spirit world.

Pablo Amaringo, a shaman and celebrated artist, was renowned for his vibrant paintings depicting his ayahuasca visions, which include spirits, animals, and cosmic landscapes.

Another Peruvian artist, Geenss Archenti, combines light-filled patterns with an earthy feel by using natural pigments he prepares from trees and medicinal plants. Archenti often paints on handmade banana leaf paper.

“Growing up in the Amazon jungle, surrounded by nature’s vibrant life, deeply influenced my artistic journey,” Archenti tells me. “My upbringing taught me to honor nature, to see its interconnectedness, and to express that in my art. The spirituality of the jungle and its ancient traditions are embedded in every brushstroke, guiding me toward a deeper understanding of both nature and self.”

Other cultures, of course, differ in their artistic styles. The Huichol people of Mexico use beadwork, yarn painting, and embroidery to create images inspired by peyote visions, which often include animals, like deer and eagles, and scenes of gods and ancestors. Yarn paintings (called nierika) are a common form of artistic expression and serve as sacred offerings.

Native Americans in the United States incorporate art that includes beadwork, painted drums, and ceremonial items used in peyote rituals. Ceremonial objects like fans, gourds, and feathers are often decorated with beadwork that reflects visions and spiritual guidance received during ceremonies.

The San People of South Africa’s rock art often depicts shamanic trance states, with images of healers, dancing, animals, and abstract patterns. These rock paintings, some of which are thousands of years old, are believed to represent visions experienced during trance states. San rock paintings in places like the Drakensberg Mountains depict a range of subjects, from animals and human figures to abstract forms that evoke altered states of consciousness.

For Aboriginal Australians, dot paintings are deeply connected to their spiritual beliefs. The dot patterns, earthy colors, and symbolic depictions of landscapes and animals represent “Dreamings” or stories that hold spiritual and cultural significance. Symbols include concentric circles (representing water holes or gathering spots) and U-shapes (indicating people sitting).

From Dreams to Drugs

In the Western world, while the inspiration for surrealism was defined through the observance of dreams, drug-induced hallucinations helped serve as the inspiration for psychedelic art. If the surrealists were fascinated by Freud’s theory of the unconscious, the psychedelic artists were moved by Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD.

In the 1950s, early artistic experimentation with LSD was conducted in a clinical context by Los Angeles–based psychiatrist Oscar Janiger. Janiger asked a group of different artists to each do a painting from the life of a subject of the artist’s choosing. They were then asked to do the same painting while under the influence of LSD. The two paintings were compared by Janiger and also the artist. The artists almost unanimously reported LSD to be an enhancement to their creativity. Eventually, around the late 1950s into early 1960, psychedelic art started to gain popularity through new forms.

This article originally appeared in Double Blind Magazine. You can read the rest of the story here.